MENU:

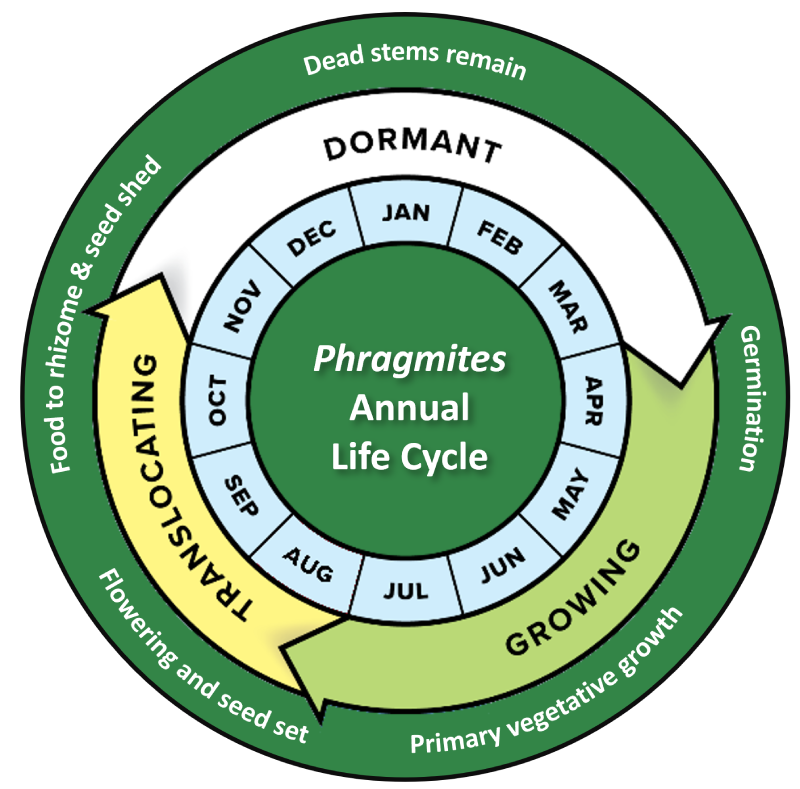

Phragmites, or common reed, exhibits different physical characteristics and perform different biological functions depending on the time of year. Understanding the annual life cycle of Phragmites is integral to successful management of the plant: the biological phase will determine which management actions are most appropriate to best reduce vigor of non-native Phragmites. Below we describe the three biological phases of Phragmites: Translocating (fall), Dormant (winter), and Growing (spring/summer). The timing of the phases described here applies broadly to the Great Lakes basin but may vary in length and/or intensity based on your local environment. The biological phases described here align with those used to plan management actions in the Phragmites Adaptive Management Framework.

Translocating Phase (August – October)

‘Translocation’ in plants refers to the movement of soluble materials from one tissue to another—often this is photosynthetic products (like sugars) moving from leaves to the belowground root structures, or rhizomes. While the direction and intensity of the translocation varies with the season, the predominantly downward flow from the leaves to the rhizomes occurs from late summer through mid-fall in preparation for dormancy and the next year of growth, although the timing can vary annually and geographically.

Flowers and seeds are formed early in this phase, appearing in distinctive puffy seed heads called a panicle, a many-branched inflorescence (Figure 1A). Each panicle is complex, containing many spikelets (Figure 1B), which contain multiple staggered florets and are composed of silky fibers, protective modified leaves, and seeds. Seeds are shed in the late translocating phase or early dormant phase.

Figure 1. A) Phragmites seed head/panicle/inflorescence. (Photo credit: Alessandro Comparoni, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons) B) Close up of a Phragmites spikelet containing florets and seeds. (Photo credit: Harry Rose, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

What to Look For: An early sign of pre-senescence translocation for Phragmites is that its panicle inflorescences (i.e., flower) will be in full bloom (Figure 2A). Once flowers have emerged, the plant’s upward growth becomes limited and downward translocation takes over. As the translocating phase progresses, the inflorescences will mature and set seed, making them look more “white and fluffy” (Figure 2B). Primary leaves on Phragmites plants will start yellowing when pre-senescence translocation is coming to an end and full senescence is beginning to set in. Once the green tissue is completely gone, translocation is done.

Figure 2 A) An early sign of late-summer translocation is that inflorescences will be in full bloom. Color variation can be due to inflorescence maturity (especially within a single patch) or genetic variability. B) As the translocating phase progresses, Phragmites leaves and stems will begin to turn from green to yellow-brown. The inflorescence will begin to set seed and become “fluffy.” (Photo Credits: GLPC).

Dormant Phase (November – March)

The dormant phase refers to the period when Phragmites’ aboveground tissues are decomposing and belowground tissues are mostly inactive. This phase typically begins in late fall and lasts into mid- to late spring. However, the start and end dates will vary annually and geographically.

What to Look For: Previously growing Phragmites is mostly or completely brown (Figure 3), and green Phragmites shoots have not yet begun emerging from the ground.

Figure 3. The aboveground portions of Phragmites will be mostly to entirely brown during the dormant phase, and there will be no new growth emerging from the ground. (Photo credit: USGS)

Growing Phase (April – June)

The growing phase refers to the period when Phragmites aboveground tissues are growing and new shoots are emerging from the ground. This phase typically begins in mid-to late spring and lasts into late summer or early fall, but the start and end dates vary.

What to Look For: Phragmites will be emerging from the ground as green shoots. During the growing phase, live Phragmites will be mostly or completely green (last year’s dead shoots may still be present; Figure 4). As the growing phase progresses, Phragmites’ aboveground tissue will continue to grow until the translocating phase begins.

Figure 4. During the growing phase, new stems emerge from the soil (A), and live Phragmites is mostly to entirely green (B). There may or may not be immature inflorescences, as these typically start later in the growing phase, and last year’s dead shoots may still be present. (Photo credits: GLPC)

During this phase, the plant may also expand horizontally to new areas. The plant may send out aboveground runners, or stolons, from which new shoots emerge (Figure 5). New shoots may also emerge from established underground rhizomes (Figure 6). Check out this page for more information about how Phragmites spreads.

Figure 5. New Phragmites shoots emerging from a stolon, or aboveground runner. (Photo credit: Stefan.lefnaer, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Figure 6. Phragmites shoots appearing from a rhizome which has been unearthed. (Photo credit: Kenraiz, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Management Implications

There is a high degree of uncertainty surrounding the efficacy and optimal timing of different management actions for reducing severity of Phragmites invasions. In fact, the goal of the Phragmites Adaptive Management Framework (PAMF), as well as many other research projects, is to determine which management actions should be used at what times to slow or prevent Phragmites growth and spread. While this is an active area of research, there are some general concepts managers may want to consider regarding timing of management in relation to Phragmites’ biological phases, namely which part of the plant’s life cycle or anatomy they want to disrupt to satisfy their management goal(s).

If a manager’s goal is to try to eliminate Phragmites, they will want to focus on management actions that are able to reduce the plant’s overall vigor, typically by reducing the capacity of the rhizomes. Since rhizomes are underground, they are more difficult to manage than aboveground biomass. There are several times of the year when the rhizomes are more vulnerable to management: the growing phase and translocating phase. In the growing phase, stored carbohydrates are lowest, having been exhausted to send up new shoots. To weaken the rhizomes further, their resources can be depleted by repeatedly removing new growth (e.g., through spading or grazing). During the translocation phase, nutrients are being moved from the aboveground leaves and stems to the rhizomes, which presents an opportunity to prevent this from happening. For example, applying herbicide during the translocating phase allows the chemicals to be transferred to the rhizomes along with the plant’s photosynthetic products, killing the rhizomes directly.

Most management actions have some seasonal considerations (see our management techniques page for more information). Mechanical removal can be performed at any time of year to satisfy different goals but can be performed before seeds are set to prevent the spread of seeds to new areas. Cutting underwater and starving plants of oxygen may perform better early in the growing season when plants require a lot of that oxygen for new growth. There are also practical reasons to consider when planning what time of the year to perform management, including timing of funding, availability of contractors or staff, field or equipment safety, water levels, or breeding periods of sensitive species.

Not all management actions need to disrupt the plant’s processes to satisfy a management goal. For example, managing a Phragmites stand during the dormant phase might not do much to harm the plant’s overall health, as the standing biomass is no longer alive and circulating energy/nutrients, and will be much less responsive to management. However, cutting or burning a dormant stand can remove standing stems that might have been blocking the view along a roadway, or were preventing access for herbicide treatment in the spring.

Management timing questions to consider:

- Is your management action being performed to target a specific part or process of the plant (e.g., rhizomes, new growth)? If so, is your management occurring at the right time of year?

- Do you want to prevent the spread of seeds?

- Do you want to disrupt the transfer of nutrients to the rhizomes?

- Can the management technique you want to use be performed safely during the time of year you’ve chosen to manage?

- Will specific timing/targeting of management actions with Phragmites lifecycle assist in minimizing impact to non-target species at your site?