MENU:

There are three lineages of Phragmites, or the common reed, found in North America, and there is significant overlap in the approximate ranges of the native and non-native strains (see our “Where is it found?” page for range maps). Stands of native Phragmites (Phragmites australis subsp. americanus) exist across the Great Lakes basin. Native Phragmites is frequently found in wetlands with high biodiversity and supplies food and nesting resources for wetland residents. Care is needed before and during management of non-native Phragmites to avoid impacting its native counterpart.

First Steps…

When managing non-native Phragmites, it is important to first determine if the plants in question are the native or invasive variety, both to protect native plants from harm and to avoid wasting invasive species management resources on a non-target species.

Where Is Native Phragmites Found?

The fine-scale distribution of native Phragmites patches is currently not well documented. According to historical University of Michigan herbarium records, native Phragmites had been found in 30 of Michigan’s 83 counties, but its current extent is less understood. Through a brief and informal survey of land managers and some on-the-ground scouting, the US Geological Survey and partners have identified multiple native patches across the Great Lakes basin, indicating that native Phragmites may be more common than initially anticipated. At some sites, non-native Phragmites was also present and, in some cases, growing right alongside the native strain. These findings raise some very interesting scientific questions, but also heighten the concern of accidental treatment of native Phragmites when targeting non-native Phragmites.

Phragmites Anatomy

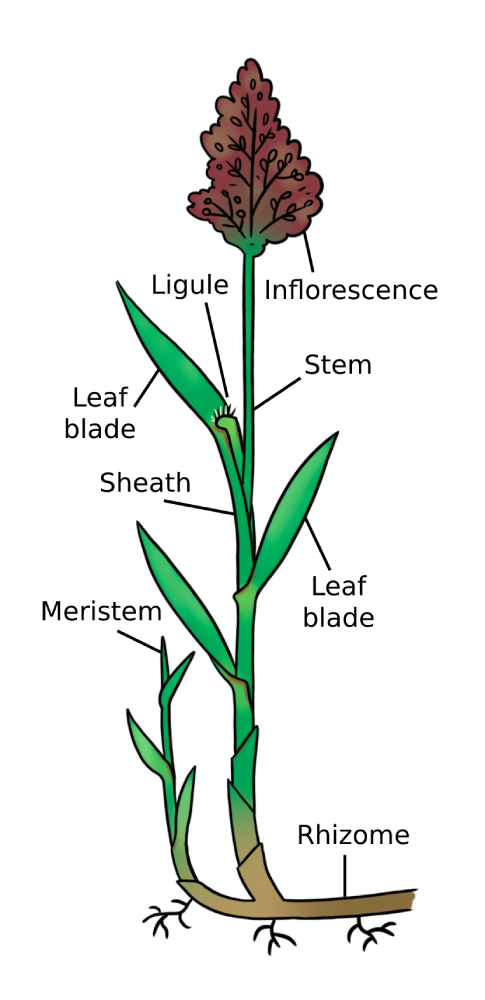

Prior to setting out to determine which strain of Phragmites you are dealing with, it helps to be familiar with the basic anatomy of the plant. This can also help you differentiate Phragmites from other lookalike species (see section at the bottom of this page).

The inflorescence, or seed head, is the puffy panicle at the top of the plant. When seeds are first produced in late summer, they appear red/purplish, but change to brown/tan later in the season.

Grasses have and interesting structure: the leaf blade is attached to a sheath that wraps around the stem.

If the sheath and the blade are pulled back, you can see the ligule, a collar-like structure at the intersection of the blade and the sheath. The ligule of non-native Phragmites is narrow and has fuzzy white hair like structures emerging from the top. See photos below for examples of ligules.

The meristem is the tip of the plant where new growth is occurring.

The rhizome is where nutrients are stored during the dormant season. Phragmites typically has dense underground rhizomes.

Tips on distinguishing native and non-native Phragmites

The following are few quick pointers to help distinguish between the two while in the field:

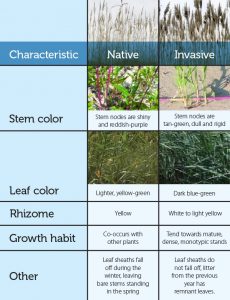

Leaf and Stem Color

Side by side, the leaves of the invasive appear bluish, while native leaves are more yellow (this determination is difficult to make when you only have one strain at hand); live stems of invasive are dull green, whereas native stems frequently appear reddish or purplish.

The picture at left shows leaves from invasive (top) and native (bottom) Phragmites australis plants. The picture on the right shows the red stems from native P. australis. Photo credits: Katherine Hollins

Leaf persistence

On dead non-native stems, leaf sheaths are difficult to remove and persist through the dormant period, whereas on dead native stems, leaf sheaths are easily removed or fall off by themselves.

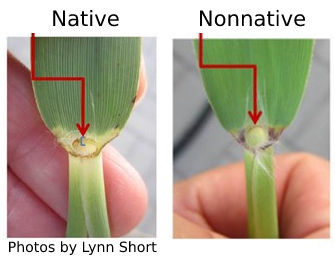

Ligule size

Non-native ligules are approximately half the length of native ligules (0.1-0.4 mm for invasive haplotype compared to 0.4-1.0 mm for native).

Photos of native and non-native Phragmites ligules. Note that the native strain has a wide ligule, and the non-native has a narrow ligule. The non-native strain may also have more/longer hair like structures.

Density

Stands of non-native Phragmites are typically very large, tall, and dense (i.e., hard to walk through easily) while native stands are usually integrated with a more diverse plant community and not as dense. This is highly variable, however, and should not be used as a lone indicator.

The pictures above show different growth patterns of invasive and native Phragmites. The left side of the photo shows a very dense senesced growth of invasive Phragmites, as opposed to the picture at right which displays the sparse stems of native Phragmites growing alongside other wetland species. Photo credits: Wes Bickford and Katherine Hollins

Seed head size

Non-native Phragmites typically has a more robust seed head (inflorescence) than native Phragmites. Native Phragmites seed heads are sometimes absent in the dormant phase, but are usually retained by the non-native form.

Native (left) seed heads are often less robust than non-native (right) seed heads. Photo: USGS Great Lakes Science Center.

Fungal spots

Native Phragmites will sometimes have black fungal dots along the stem, while non-native stems are typically spot-free. This character is highly variable.

Photo by R. E. Meadows. Photo from the Phragmites Field Guide: Distinguishing between native and exotic forms of Common Reed (Phragmites australis) in the United States.

Summary of characteristics

The chart below provides a brief overview of characteristics to look for when distinguishing between native and non-native Phragmites.

Source: Michigan Sea Grant.

Lookalike Species

Non-native Phragmites can be difficult to distinguish from native Phragmites, but it can also be difficult to tell apart from other plant species. If you want to brush up on your general plant identification skills, check out the list of lookalike species below and resources on plant identification.

- Reed canary grass (non-native / native / hybrid): Link1 / Link 2

- Bluejoint (native)

- Lake sedge (native)

- Rattlesnake grass (native)

- Prairie cordgrass (native)

- Giant foxtail

- Smooth brome (non-native)

- Lyme grass (invasive)

- Wild rice (native)

Identification Resources

There are many resources online and in print to help aid in distinguishing between the native and non-native Phragmites.

Some great examples can be found at:

- Phragmites Field Guide: Distinguishing between native and exotic forms of Common Reed (Phragmites australis) in the United States

- Native or Not? Quick Guide

- MISIN’s Phragmites ID training module

- Pages 3-5 of the Guide to the Control of Native and Non-Native Phragmites by the Michigan DEQ

- Winter Identification of Native and Exotic Phragmites

- The GLPC’s Reference Library

Video Identification Resources

Watch field experts reference the identification points of native and non-native Phragmites

Native or Introduced? Identification of Phragmites lineages in North America

This presentation by Dr. Kristin Saltonstall (Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute) provides great detail on the identifying characteristics of native and non-native Phragmites, including characteristics that should not be used. 27 minutes, 2015.

Dr. Dan Carter Explains How to Identify Native Phragmites

Dr. Dan Carter (Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission) goes into the field to show how to identify non-native and native Phragmites during the dormant season (although many of these tips work any time of year). 22 minutes, 2016.

Genetic Identification

Information on genetic identification techniques of Phragmites and expert contacts.

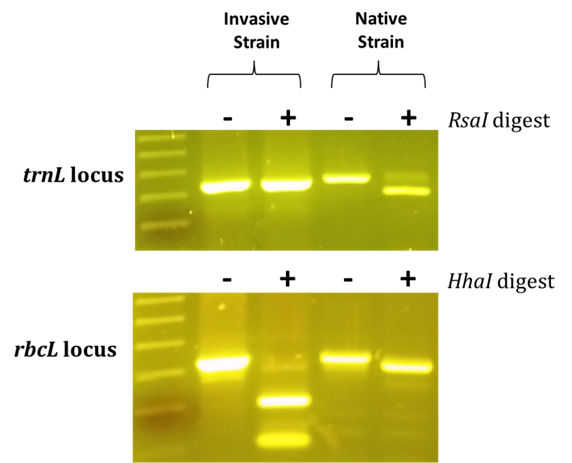

In many cases it can be difficult to distinguish between native and non-native Phragmites based on morphological characters alone. Using methods developed by Saltonstall (2002, 2003), leaf tissue DNA can be sequenced or analyzed with a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay to differentiate the native and non-native haplotypes.

To identify the differences in fragment lengths between native and non-native DNA sequences, a digest is performed using DNA-cutting enzymes to cut genetic material at specific nucleotide sequences. This digested material is then processed through gel electrophoresis. Gel electrophoresis uses electric current to move segments of cut DNA through a gel medium where larger segments move slower than smaller fragments and allows for comparison of sequences of interest with control sequences.

Phragmites Haplotypes

Haplotypes can be described as “a set of DNA variations, or polymorphisms, that tend to be inherited together” (Genetics Home Reference 2015, Saltonstall 2016). This type of genetic variation aids in tracking invasive species and can help us differentiate between native and cryptic invaders (non-native species that are almost morphologically identical to their native counterparts). Identifying native and introduced species can also have implications for management at the local or regional level.

Phragmites haplotypes are identified using maternally inherited chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) which has predictable patterns of inheritance and variation. Saltonstall 2002 and 2003 provided a system for haplotype taxonomy using specific locations within the cpDNA that were compared in samples of Phragmites across different populations to determine patterns of Phragmites historical introduction and spread across the globe. Work by many researchers has been done since then and in a more recent update, Saltonstall 2016 lists 58 haplotypes of Phragmites identified around the world.

In the US, the primary invasive Phragmites lineage has been identified as Haplotype “M”, which was likely introduced to North America from Europe. It now dominates Phragmites stands in much of North America and is common across the Great Lakes region. Notably, there is also variation within these haplotype designations; for Haplotype M there are at least 5 additional intra-haplotypes, of which, only Haplotype M1 was found present in the US along the Gulf coast but was present in the Middle East and North Africa as well (Saltonstall 2016). Native Phragmites stands in the Great Lakes region have been found to have haplotypes E, G, and S that can be analyzed through restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assays and link them to other native haplotypes in North America.

For more information on Phragmites haplotypes and genetics, explore the National Center for Biotechnology Information, an online repository of genetic information.

- Saltonstall, K (2002) Cryptic invasion by a non-native genotype of the common reed, Phragmites australis, into North America. Proc Nat Acad Sci 99:2445–2449. Doi: 10.1073/pnas.032477999

- Saltonstall, K (2003) A rapid method for identifying the origin of North American Phragmites populations using RFLP analysis. Wetlands 23(4):1043-1047.

- Saltonstall, K (2016) The naming of Phragmites haplotypes. Biol Invasions 18, 2433–2441. doi: 10.1007/s10530-016-1192-4

Genetic Diagnostic Services

If you need genetic confirmation for whether your Phragmites is native or invasive, then consider contacting one of the following cooperating laboratories:

- Doug Wendell, Ph.D., wendell@oakland.edu Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan.

- PHYTOID, Tippery Lab, University of Wisconsin- Whitewater

The above photos are of the resultant RFLP gels showing the DNA polymorphisms (or differences) between invasive (left) and native Phragmites (right). “-“ indicates the control DNA with known length and sequences, and “+” indicates the DNA plus the digest. The invasive DNA is not cut by the RsaI digest, but is cut by the HhaI digest, whereas the native is cut by the RsaI digest, and not cut by the HhaI digest.

Native and Non-native Phragmites Photos

Check out the gallery below to see photos of native and non-native Phragmites. Use the page numbers below the images to see additional images.

Native vs non-native

Physical differences can be used to distinguish between native and non-native Phragmites.

Witches Broom

Sometimes if treated with herbicide Phragmites grows back in the stunted form seen here

Non-native Phragmites seed heads

The inflorescence (or seed head) of non-native Phragmites can vary in color